The Phantom Island of Hy-Brasil in Irish Myth & Fable

Anthony Murphy looks at the fascinating story of the phantom island of Hy-Brasil in the Atlantic, which is said to become visible to mainlanders once every seven years, retold by author and antiquarian W.G. Wood-Martin.

In Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland: A Folklore Sketch (1902), W.G. Wood-Martin has a section dealing with 'Phantom Lands'. One of those phantom lands is the fabled island of Hy-Brasil, said to be located in the Atlantic Ocean west or southwest of Ireland. It was once marked on medieval maps, but no such island exists today.

Wood-Martin tells us that in the 17th century, Roderick O'Flaherty said that the phantom island of Hy-Brasil – marked on many old charts near the west coast of Ireland – was, in his time, "often visible". The subject has inspired several poets with beautiful fancies which have been woven into pathetic ballads. Gerald Griffin describes it thus:

On the ocean that hollows the rocks where ye dwell

A shadowy land has appeared, as they tell:

Men thought it a region of sunshine and rest,

And they called it Hy-Brasil, the isle of the Blest.

From year unto year on the ocean's blue rim,

The beautiful spectre showed lovely and dim:

The golden clouds curtained the deep where it lay,

And it looked like an Eden away, far away!

Many attempts were made to discover this fabled island. Leslie, of Glaslough, described as a "wise man and a great scholar", was so imbued with belief in its real existence that he solicited a grand of the isle from Charles I. Edmond Ludlow, the celebrated republican, escaped to the Continent in a vessel chartered at Limerick, to sail in search of Hy-Brasil; and so form then was belief in the actual existence of this enchanted island, that the captain of the ship was allowed to depart unquestioned.

A rare work entitled La Naviation l'Inde Orientale, printed at Amsterdam in the year 1609, contains a map on which two islands, styled Brasil and Brandon, are marked as actually existing off the Irish coast. Fig. 67 is a reproduction of that portion of the place above referred to. Fig. 68 is a chart by the French Geographer Royal made in the year 1634, on which the island of Hy Brasil is also distinctly marked.

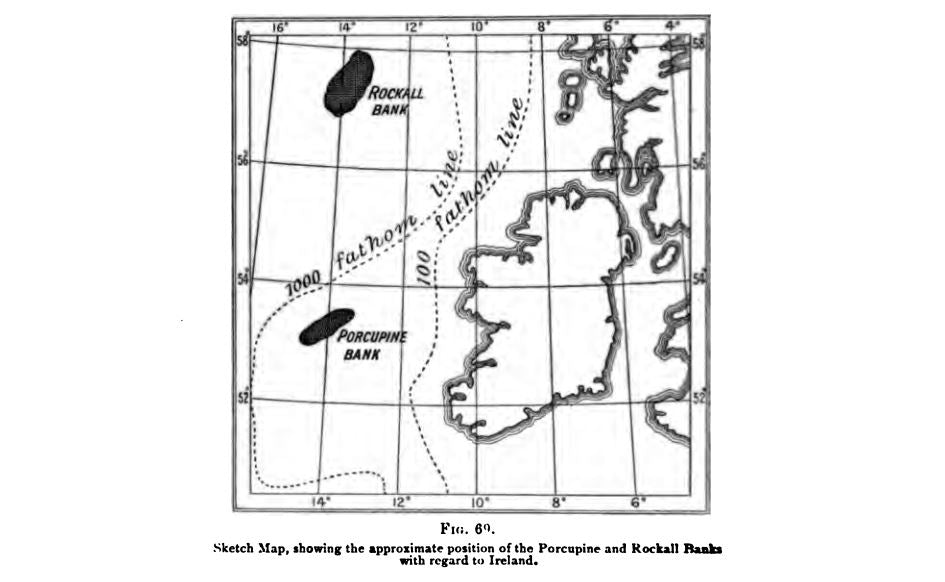

Fig. 69 shows the approximate position of the Porcupine and Rockall Banks with regard to Ireland. Rockall is still, in part, above the waters, and the rocky pinnacle it presents is a great danger to navigation. It is probably the last fragment of the island of Brandon, and the Porcupine Bank may represent the site of the now phantom land of Hy-Brasil.

On the 2nd March, 1674 (it is well to be very particular as to the exact date), a Captain Nesbett discovered, disenchanted, and actually landed on Hy-Brasil, which he also partially explored. The disenchantment was effected by lighting a fire upon it. "Since then," says the writer, "several godly ministers and others are gone to visit and discover them" (i.e., the inhabitants), but as the author had heard no news of their return, he says he awaits with becoming patience further particulars. We are left in ignorance as to whether these were ever given, but from a silence of upwards of two centuries the probability is, that the disenchantment wrought by the lighting of the fire was but temporary; that the "godly ministers and others" have met with the fate of Ossian of old, but doubtless when the day of their release arrives we shall hear of strange discoveries. The pamphlet, purporting to give an account of the discovery of Hy-Brasil, obtained a good circulation in London in 1675.

The existence of a land which would restore the aged to the full vigour of youth was of world-wide belief, but all attempts to discover this land necessarily ended in disappointment; nevertheless, the strange spirit of adventure thus engendered, laid open to view countries which might otherwise have remained for centuries unknown. A country of indefinite magnitude, called Brasil, is marked on maps made before or about the time of Columbus. It is represented south of another island which, it is thought, represents the supposed position of the Scandinavian settlements of Vineland; for, although we designate the American continent the "New World", it was apparently known to those ancient rovers of the sea.

O'Flaherty mentions the appearance, in 1161, of "fantastical ships" in the harbour of Galway sailing against the wind; and Hardiman, editor of the above work, remembered having seen a well-defined aerial phenomenon of the same kind from a hill near Croaghpatrick in Mayo, on a serene evening in the autumn of 1798. Hundreds who also witnessed the scene looked upon it as supernatural, but soon afterwards it was ascertained that the illusion had been produced by the reflection of the fleet of Admiral Warren which was then in pursuit of a French squadron off the west coast of Ireland. In like manner may not the optical illusion noted in the Irish annals as occurring in the year 1161, in the harbour of Galway, have been produced by the reflection of a distant fleet of Northern war-galleys.

Belief in the existence of Hy-Brasil doubtless gave rise to the traditional transatlantic voyage of St. Brendan (spelled Brandion on the map, fig. 67), an adventurous ecclesiastic, styled "the Navigator", who passed seven years away from Ireland on a distant island. St. Brendan has been styled "the Sindbad of clerical romance"; and so firm a hold of men's minds had the exploits of this Christian Ulysses at one time acquired, that islands, supposed to have been discovered by him, became subjects of treaty.

It is not improbable that, at a later period, his adventures stimulated navigators to attempt discoveries across the western ocean. St. Brendan sailed about on a huge rock, which he finally abandoned on the coast of Donegal. St. Declan's Rock may still be seen on the strand in Ardmore bay. This "boat" is computed to weigh about three tons. It navigated itself, on the surface of the sea, from Rome, carrying, by way of cargo, nine bells, and the curious ship reached land with its load most opportunely, just as St. Declan was in dire want of a bell to celebrate Mass.

There is a curious MS. (manuscript) on medical subjects in the Royal Irish Academy, traditionally believed to have been originally obtained by a native of Connemara, transported by supernatural means to the enchanted isle of Hy-Brasil, where he received full instructions with regard to all diseases, their treatment and cure, and was presented, on leaving, with the MS. to guide him in his medical practice. So late as the year 1753, there is in The Ulster Miscellany a curious satire entitled "A voyage to O'Brazal, a submarine island lying off the coast of Ireland."

O'Flaherty, writing in 1684, states that: "From the isles of Aran and the west continent often appears visible that enchanted island called O'Brasil, and in Irish Beg-Ara, or the Lesser Aran, set down in cards of navigation; whether it be real and firm land, kept hidden by special ordinance of God, as the terrestrial paradise, or else some illusion of airy clouds appearing on the surface of the sea, or the craft of evil spirits – is more than our judgments can sound out."

The Rev. Luke Connolly, writing in 1816, states that he received minute descriptions of extraordinary Fata Morgana which appeared along the sea-coast near the Giant's Causeway, from those who saw the beautiful illusions on various summer evenings: – "Shadows resembling castles, ruins, and tall spires darted rapidly across the surface of the sea, which were instantly succeeded by appearances of trees, lengthened into considerable height; these shadows moved to the eastern part of the horizon, and at sunset totally disappeared. These phenomena have given rise to various romantic stories. A book still extant, printed in 1748, and written by a person who resided near the Giant's Causeway, gives a long account of an enchanted island, annually seen floating along the county of Antrim coast, which he fancifully calls the 'Old Brazils.' It is supposed by the peasants that a sod from the Irish terra firma, thrown on this island, would give it stability; but though several fishing boats have gone out, at different times, provided with this article, it has hitherto eluded their vigilance."

Belief in the existence of the island of Hy-Brasil may have arisen through these optical illusions, which are not so very infrequent as is generally supposed. A correspondent writes – "I myself, upwards of half a century ago, saw a wonderful mirage resembling that lately described as having been visible off our Tireragh coast (county of Sligo); and had I been looking on the bay for the first time, nothing could have persuaded me but that I was gazing at a veritable city – a large handsome one too, trees, houses, spires, castellated buildings, &c." The enchanted island of Hy-Brasil was again seen off the coast of Sligo (as above alluded to) in the year 1885; the vision forebodes – so it is alleged – national trouble.

There is also another consideration with regard to this phenomenon which has not been sufficiently taken into consideration. We cannot see objects below the horizon, but sometimes, owing to the peculiar state of the atmosphere, the rays of light are so bent that, when they reach the eye, they make distant objects visible. For instance, place a coin in a saucer, so as to be hidden from observation, pour water into the vessel, and though the coin is below the horizon it becomes at once visible. This reflection, usually seen across water, is among sailors known as "looming"; the objects that "loom" are magnified vertically, and seem unnaturally near. Snowdon, in Wales, is thus occasionally seen by pilots in Dublin Bay, though it is over one hundred miles distant.

P.W. Joyce says that "the Gaelic tales abound in allusions to a beautiful country situated under the sea – an enchanted land sunk at some remote time and still held under spell. In some romantic writings it is called Tír-fa-tonn, 'the land beneath the wave'; and occasionally one or more of the heroes find their way to it . . . The island of Fincara and the beautiful country seen beneath the waves by Maildun are remnants of the same superstition." This romantic delusion is not confined to Ireland. Belief in it is found in the mythology of almost every race; and "although all evidence points in an opposite direction, and rather to an evolution from lower to higher conditions everywhere, the idea that a paradise lies behind us will probably remain in the chronic fiction of humanity so long, at least, as to the individual bygone troubles appear small comparatively when dwarfed by distance in the retrospect, and while the memory of age continues to dwell regretfully on long vanished scenes that may have owed their brightness chiefly to the summer atmosphere of youth."

The concord of classic and Irish tradition is remarkable; in both cases, somewhere far away in the western ocean, there was a country which passed under various names; and that this was one of the elysiums of the primitive Irish, as well as of classic writers, is very clear. It appears to have corresponded to the "Land of the Saints" of early Irish Christianity, where the souls of the blessed await the Day of Judgment, even as the "Land of the Living" was to the Pagan Irish their happy "Spirit Home". The general traditions of pagan peoples place the point of departure from this world, and entrance to the next, always to the west, and the journey lay westward. For instance, in the mythological legend of the adventures of Condla Ruad the hero embarks in a currach made of pearl, and glides away on the boundless ocean, watched by his friends with straining and streaming eyes until the skiff disappears in the glow of the great "white sun" on its voyage westward to the "Island of the Blessed," to

"A land of youth, a land of rest,

A land from sorrow free;

It lies far off in the golden West,

On the verge of the azure sea."