Scribes and kings: religion, politics and the medieval manuscripts of Ireland

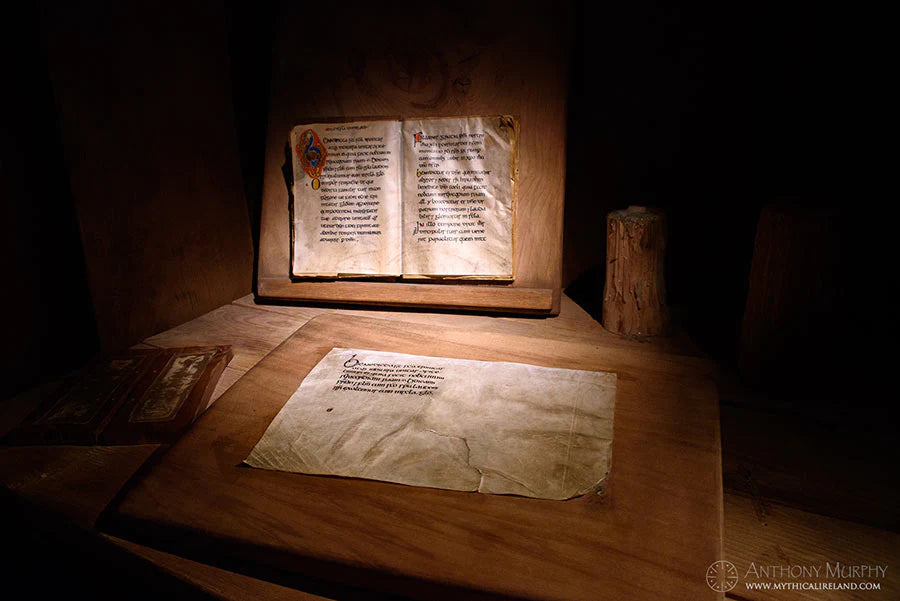

It is a remarkable fact that a great deal of Ireland’s mythological material from past ages available to the student of mythology and fable today was written down in the Middle Ages by Christian scribes based in monasteries in different parts of the island.

The mythological traditions, especially those dealing with the pre-Christian (‘pagan’) notion of the otherworld, “were taken up with enthusiasm and adapted in various lyric forms by the monastic writers”.[i] And we are very fortunate, and indeed glad, that they chose to do so.

“It is an interesting thought,” wrote Celtic scholar Proinsias Mac Cana, “that, had it not been for the tolerance and intellectual curiosity of the monastic literati, very little of the old literary heritage would have been ours now to enjoy.”[ii]

Their heterodoxy is our boon.

The scribes are copying to preserve a heritage that has been handed down, not often composing afresh; and so it is that almost all our early texts are anonymous, or have been given some legendary attribution – to Find Mac Cumaill or to Colum Cille or St. Benignus.[iii]

Medieval scholars have long been aware of the fact that the “old belief system” coexisted with Christianity in Ireland for a number of centuries in the early medieval period.[iv] While Christian “literate culture” inspired many of the early vernacular Latin and Irish texts, it is still possible to extrapolate some of the genuine pre-Christian or pagan religious practices from these texts.[v]

Mael Muire Mac Célechar, principal scribe of Lebor na hUidre, The Book of the Dun Cow, at Clonmacnoise, “would have had access to the oral tradition within the bardic schools, which had kept knowledge of the ancient legends alive”.[vi]

A later “authoritative contributor” to Lebor na hUidre made corrections, interpolations and added notes, and in places “he so vigorously erased some of the other scribes’ work to make room for his own that he rubbed holes in the vellum”.[vii]

The material which makes up Lebor na hUidre was drawn from early sources including manuscripts from other monasteries which has been described as “the product of the heroic age of Irish literature, that time between the seventh and ninth centuries when king and monk and poet co-operated in a passion of memory and creation to build up the legend of the Irish past”.[viii]

The main aim of Lebor na hUidre was to preserve ancient pre-Christian lore, according to Irish manuscripts expert Michael Slavin, but because the scribes were religious men writing in a monastery environment, it should be no wonder that ”material of a pious nature was interspersed”.[ix]

The Book of Leinster, which was actually properly titled Lebor na Nuachongbala, included a note at the conclusion of the epic story Táin Bó Cuailgne, written by the sole scribe of the work, which read: “I place no credence in this story or fable, for in part it contains the deceptions of demons, in part the invention of poetry, in part the appearance of truth and in part not, and in part the delectation of fools”.[x]

The material of the Book of Leinster – mythic, historic and poetic – represented the collection of material by “a scholar anxious to put together some of the chief literary works of his time”.[xi]

It is helpful to understand too that while the compilers of the medieval manuscripts were ostensibly Christian, some of them had a heritage that stemmed from pre-Christian times. The Yellow Book of Lecan, for example, was compiled by a member of the Mac Fir Bisigh family at Lecan in County Sligo. Such families were “more than historians, for they carried in their genes a deep and precious strain of wisdom and learning that had its roots back in Druidic times. Their aura of sacredness came not from ordination in the Christian Church but from an inheritance, a conviction and a reputation for knowing that had its origin back in pre-Christian Ireland.”[xii]

Following the arrival of Saint Patrick, they found refuge in the monastic structures of the Celtic church, but after the reform of St. Malachy in the 12th century, they were perhaps less than welcome within the walls of the great Cistercian and Benedictine abbeys. Thus were the great bardic Brehon Law and historical schools of the O’Duignans, MacEgans, O’Dalys and Mac Fir Bisigh established.

An inauguration ceremony of the O’Dowds, which involved the Mac Fir Bisighs, described in the Great Book of Lecan contains “a delightful mixture of Gaelic Druidic taboos and the salvation beliefs of Christianity”.[xiii] The two world views – paganism and Christianity – could, it seems, coexist.

Perhaps the best example of a narrative from an Irish medieval manuscript that combines apparently irreconcilable cultures – Christian and ancient druidic on one hand, and Anglo Norman and ancient Celtic on the other – is the tract in the 15th century Book of Lismore called Acallam na Senórach, commonly known in English as The Colloquy of the Ancients or Tales of the Elders of Ireland. In it, Saint Patrick and his followers are joined by ancient leaders of the Fianna (dating from several centuries previously) – Oisín and Caoilte – as they make their missionary journey around Ireland. Patrick is “distracted from his Christian duties as he listens to tales of times past when the Fianna were at the height of their powers under the leadership of Fionn”.[xiv] One of many overarching themes of Acallam na Senórach is “the general harmonizing of the values of the warrior élites, the royal dynasties, and the Church”.[xv]

Ecclesiastical scribes were often bound to political duties which might have grated with their Christian conscience. As one book on early medieval Ireland says, “It may be unwise to make too clear a distinction between politics and religion. Everything that we know about kingship throughout the world shows that the creation of a king is a religious act.”[xvi]

“Since this institution was of such fundamental importance to the people, its Christianisation must have taxed the early clergy to the limit.”[xvii]

Ecclesiastical foundations such as the monasteries at Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, and Clonard Abbey, Co. Meath, had close associations with kings and political dynasties – Clonmacnoise with the kings of Connacht, and Clonard with various competing political dynasties.

At Cashel, the early 10th century king Cormac mac Cuilennán was also a bishop![xviii]

“Powerful patrons endowed the large monasteries, placed members of their kin in important positions in these institutions, and thus created great ecclesiastical lordships that owned land, people and smaller churches.”[xix]

In the eighth century, as kings became more closely affiliated with the church, ecclesiastics became increasingly entangled in secular affairs.[xx]

“Churchmen,” says medieval scholar Matthew Stout, “took part in battles and the great monastic sites waged war against each other in the midlands.”[xxi]

The coalescence of church and state can be seen, says Stout, in the writing of secular tales within monasteries. The Táin Bó Cuailnge, for instance, the great epic tale of the Cattle Raid of Cooley and the battle for the bulls between Queen Medb of Connacht and the Ulster armies, was first written down at this time.

While it would be wrong to suggest that the medieval Irish poets and brehons were “crypto-pagans”, i.e. a pagan who maintains a pretence of adherence to Christianity while observing pre-Christian practices in private, “by virtue of their very office, which was to transmit the senchas or tradition, they consciously or unconsciously retained many druidical traits”.[xxii]

In fact, Old Irish literature obtained its luxuriance and originality “from the fruitful collaboration of monk and fili”.[xxiii] (Fili is a poet or ‘seer’.)

The early annals – all of them – were “entirely the product of the monastic schools”.[xxiv] All of the great monasteries kept annalistic records in detail, and the monks “felt no scruples about recording” even the battles between the monastic communities.[xxv] Only the later chroniclers, Michael O’Clery and his associates compiling the famed Annals of the Four Masters in the first half of the seventeen century, engaged in editorial censorship by dutifully “cutting out entries which they felt might be piis auribus offensum”[xxvi] (offensive to pious ears).

The heroic epic stories, the tales of voyages and visions allegedly emanating from Ireland’s pagan past, were committed to vellum either in the monasteries or by those who had received a monastic education.[xxvii] But the myths were “viewed through the prism of monastic scribes, to meet the taste of a secular audience of the educated privileged classes”.[xxviii]

Against this background, it would be perhaps gullible to expect those overtly pagan myths – which had previously been transmitted orally – to be propagated unaltered by ecclesiastical scribes.

The infiltration or ingression of Christian doctrine into overtly pagan mythology is regularly seen in the medieval manuscripts, perhaps as a means of attempting some sort of reconciliation between the two. In the Metrical Dindshenchas story about Dowth, for instance, which records the story about how and why the great monument at Brú na Bóinne was constructed, the comparison of the mound with the “Tower of Nimrod”[xxix] would appear to be a clear incursion of Old Testament perspectives into pre-Christian onomastic lore.

“It is well accepted,” says Dr Lara Cassidy of Trinity College Dublin, “that biblical narratives and local pagan mythology were woven together in works like the Dinshenchas. Untangling the two is a complex task.”[xxx]

The frequent mention of Judgement Day in the old written myths is clearly an infiltration of Christian eschatological belief into the stories. In Baile in Scáil, ‘The Phantom’s Frenzy’, a regnal prophecy composed in the ninth century and revised in the eleventh,[xxxi] Conn ascended the rampart of Tara before sunrise and stood on a stone that screamed beneath his feet so that its cry was heard in Tara and all of the plain of Brega. His druid told him the name of the stone was Fál, and that it would remain in the land of Tailtiu “until the Day of Judgement”.

“The number of cries which the stone uttered,” the druid told Conn, “is the number of kings that there will be of your race until the Day of Judgement.”[xxxii]

The origin poem about Dowth given under Cnogba (Knowth) in the Metrical Dindshenchas prophesizes that, after the men of Érin abandon building the great monument, it would remain without addition to its height – “it shall not grow greater from this time onward till the Doom of destruction and judgment”.[xxxiii]

It is clear that, when a particular myth proved excessively repugnant or challenging to the scribe’s own beliefs or doctrine in certain details, alteration, insertions and even perhaps expunction of particulars were practised.

“It was,” says James Henthorn Todd in the introduction to his translation of Cogadh Gaedhel Re Gallaibh (The War of the Irish With the Vikings), “unfortunately the custom of Irish scribes to take considerable liberties with the works they transcribed. They did not hesitate to insert poems and other additional matter, with a view to gratify their patrons or chieftains, and to flatter the vanity of their clan.”[xxxiv]

“It is to be feared,” he continues, “that for the same reason, they frequently omitted what might be disagreeable to their patrons, or scandalous to the Church…”[xxxv]

In fact, scholars submit that the entire work of Cogadh Gaedhel Re Gallaibh was, in essence, a panegyric (a text in praise of someone) on the Dalcassians (the Dál Chais, a small tribe of northwest Munster) and particularly Brian Bóramha (Brian Boru, who became high king of Ireland in 1002) and their achievements against the Vikings.[xxxvi] A corresponding tract called Caithréim Cellacháin Chaisil (‘The Triumph of Cellachán of Cashel’) is a pseudo-historical work of propaganda in praise of Cellachán, a king of Munster of the Eóganacht clan based at Cashel, ancestor of the MacCarthys and the O’Callaghans, written in the 12th century but relating to supposed events of the 10th century.[xxxvii]

On occasion, the scribe would add a note or gloss rather than directly interfering in the tale. At the end of the Book of Leinster version of the Táin Bó Cuailnge, the scribe wrote “Amen” and “A blessing on everyone who will memorize the Táin faithfully in this form, and not put any other form on it.”[xxxviii] One might have been forgiven for thinking that the scribe enjoyed the story. But not so, because he followed it up with these written remarks:

“I who have copied down this story, or more accurately fantasy, do not credit the details of the story, or fantasy. Some things in it are devilish lies, and some are poetical figments; some seem possible and others not; some are for the enjoyment of idiots.”[xxxix]

A more conservative, ascetic and perhaps fundamentalist branch of the church, known as the Céli Dé (clients or servants of God; Céli Dé is anglicised to Culdee[xl]) emerged towards the end of the eighth century. This was a movement which was clearly concerned with a shift away from the overt association between the early medieval church and the secular dynastic chiefs. This movement’s purview was to “counterbalance a tendency towards laxity in the older churches”[xli] and celebrated what it saw as a victory of the Irish Church over paganism:[xlii]

The old cities of the pagans,

wherein ownership has been acquired

by long use, they are waste without

worship, like Lugaid’s House-site. The cells that have been taken

by pairs and by trios, they are Rome’s

with multitudes, with hundreds,

with thousands. Heathendom has been destroyed,

though fair it was and widespread:

the kingdom of God the Father has filled

heaven, earth and sea.[xliii]

Ironically, heathendom, far from being obliterated, found its old lore preserved on the leaves of vellum by monks and scribes of Ireland’s medieval monasteries. The fact that it had been blended with Old Testament narratives so that it would sit better with church authorities mattered little. This lore, myth and fable had been propagated, or at least preserved, rather than expunged, thanks to those dedicated Christian writers, who laboured long and hard to transcribe them.

“Early medieval Irish society … had its own creation myths and it had constructed and written down in the languages of the people and of the Church the direct link between the Irish people and the Old Testament. The Irish language itself was regarded as being comprised of ‘what was best of every language’ created at the Tower of Babel.”[xliv]

Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Book of the Taking of Ireland (commonly called the Book of Invasions), is a substantial quasi-historical work that attempts to trace the origins of all of the various peoples who arrived into Ireland in the remote past. It begins with a chronicle of the dispersal of the nations and the first of the arrivals into Ireland includes Cessair, the granddaughter of the Biblical Noah, who has been refused a place on the Ark and comes to Ireland on Noah’s advice.

RAS Macalister, who translated Lebor Gabála Érenn, said that it begins with a Liber Occupationis Hiberniae, which he describes as “a sort of quasi-historical romance, with no backing either of history or tradition; an artificial composition, professing to narrate the origin of the Gaedil onward from the Creation of the World (or the Flood), their journeyings, and their settlement in their “promised land”, Ireland.”[xlv]

“This production,” Macalister says, “was a slavish copy, we might almost say a parody, of the Biblical story of the Children of Israel.”[xlvi]

A 12th century reaction of the authorities to the secular control of churches was a work of ecclesiastical reform initiated from abroad, it seems, by Pope Gregory VII, and at home by St. Malachy, resulting in the Synod of Ráth Bresail in 1111, which marked the transition of the Irish church from a monastic to a diocesan and parish-based organisation, and the Synod of Kells in 1152, which further defined the diocesan system and increased the number of archbishops from two to four.[xlvii]

The primary purpose of this whole movement of reform, according to one scholar, was “the prizing free of churches from control by local secular families who had turned the churches and the church property into private possessions, passed on to their children, like a field or a horse, by inheritance”.[xlviii]

This period of reform represented something that historians refer to as a twelfth-century renaissance,[xlix] but it had an antecedent in the eleventh century, partly driven by the efforts of Brian Boru following a very chaotic and bloody episode during which the Vikings, and sometimes Irish kings, had repeatedly raided, plundered and burned the monasteries, which were centres of learning and civilisation.[l] After making a circuit of Ireland to receive the pledges of all the provincial or local kings, Brian:

… erected also noble churches in Erinn and their sanctuaries. He sent professors and masters to teach wisdom and knowledge, and to buy books beyond the sea, and the great ocean, because their writings and their books in every church and every sanctuary where they were, were burned and thrown into the water by the plunderers, from the beginning to the end, and Brian, himself, gave the price of learning and the price of books to every one separately who went on this service.[li]

The radical reform of the church in the 12th century, initiated by St. Malachy (the founder of the Cistercian monastery at Mellifont Abbey, Co. Louth) and authorised by the synods of Ráth Bresail and Kells, began a long period marking the decline of storytelling and saga among the learned classes which was also quite adversely affected by the coming of the Normans before the end of that century.[lii]

The change brought about a transfer of the heritage of manuscript tradition from the monasteries to the lay scholars, the fili of ancient times, who later appear in separate schools of poets, historians, lawyers and leeches.[liii]

From then on, “kingly storytelling … gave way to storytelling of a less exalted nature”.[liv]

But greater disaster was to come, in the form of the calamitous conclusion to the Nine Years’ War with the defeat of the Gaelic lords and their Spanish allies at the Siege of Kinsale, the signing of the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603,[lv] the ensuing Flight of the Earls in 1607, and the Plantation of Ulster. But that’s a story for another day.

Footnotes & references

[i] Mac Cana, Proinsias (1969), ‘Irish Literary Tradition’, in A View of the Irish Language, edited by Brian Ó Cuív, Rialtas na hÉireann, p. 40.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Dillon, Myles (1961), ‘Literary Activity in the Pre-Norman Period’, in Seven Centuries of Irish Learning 1000-1700, edited by Brian Ó Cuív, Stationery Office Dublin, p. 30.

[iv] Bhreathnach, Edel (2014), Ireland in the Medieval World AD 400-1000: Landscape, kingship and religion, Four Courts Press, p. 131.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Slavin, Michael (2005), The Ancient Books of Ireland, Wolfhound Press, p. 6.

[vii] Ibid., p. 7.

[viii] Flower, Robin (1994), The Irish Tradition, Lilliput Press, Dublin, p. 100.

[ix] Slavin, op. cit., p. 15.

[x] Dunn, Charles, ‘Ireland and the Twelfth-Century Renaissance’, University of Toronto Quarterly, Vol. XXIV, No. 1 (1954), p. 71.

[xi] Dillon (1961), op. cit., p. 32.

[xii] Slavin, op. cit., p. 53.

[xiii] Ibid., p. 67.

[xiv] Slavin, op. cit., p. 73.

[xv] Dooley, Anne and Roe, Harry (2008) [1999], Tales of the Elders of Ireland, Oxford University Press, viii.

[xvi] Breathnach, Edel et al (2005), The Kingship and Landscape of Tara, Four Courts Press for The Discovery Programme, p. 13.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] For more about Cormac and Cashel, see Byrne, Francis J., (2001) [1973], Irish Kings and High-Kings, Four Courts Press, chapters 9 and 10.

[xix] Bhreathnach (2014), p. 183.

[xx] Stout, Matthew (2017), Early Medieval Ireland 431–1169, Wordwell, p. 111.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Byrne (2001), p. 13.

[xxiii] Ibid., p. 14.

[xxiv] Binchy, D.A. (1961), ‘Lawyers and Chroniclers’, in Seven Centuries of Irish Learning 1000-1700, edited by Brian Ó Cuív, Stationery Office Dublin, p. 59.

[xxv] Ibid., p. 68.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Stout (2017), p. 115.

[xxviii] Ibid., p. 116.

[xxix] Gwynn, Edward (1924), The Metrical Dindshenchas Part IV, Royal Irish Academy Todd Lecture Series Volume XI, pp. 271-3.

[xxx] Musgrove, David, Medieval(ish) matters #9: Do early medieval Irish texts shed light on prehistoric incest? https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/do-early-medieval-irish-texts-shed-light-prehistoric-incest/ Retrieved 7th July 2020.

[xxxi] For a translation of the story, see Murray, Kevin (2004), Baile in Scáil, ‘The Phantom’s Frenzy’, Irish Texts Society. For a summary and discussion, see Carey, John (2005), ‘Tara and the Supernatural’ in Bhreathnach, Edel, et al (2005), The Kingship and Landscape of Tara, Four Courts Press for The Discovery Programme.

[xxxii] Carey (2005), p. 37.

[xxxiii] Gwynn, Edward (1913), The Metrical Dindshenchas Part III, Royal Irish Academy Todd Lecture Series Volume X, p. 47.

[xxxiv] Todd, James Henthorn (2018) [1867], Cogadh Gaedhel Re Gallaibh, Franklin Classics Trade Press, p. XVI.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Ryan, John, S.j. (1961), ‘The Historical Background’, in Seven Centuries of Irish Learning 1000-1700, edited by Brian Ó Cuív, Stationery Office Dublin, p. 15.

[xxxvii] Ibid.

[xxxviii] Cahill, Thomas (1995), How the Irish Saved Civilisation, Sceptre, p. 160.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] O’Dwyer, Peter (1995), Celtic Monks and Culdee Reform, in An Introduction to Celtic Christianity, edited by James P. Mackey, T&T Clark, Edinburgh, p. 141.