The division of Ireland - a mythic theme and historic reality

Ireland has long been divided. Today, there is an invisible border that separates the Republic of Ireland from Northern Ireland. In mythology, the division of Ireland into provinces began with the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Book of the Takings of Ireland, a pseudo-historical cosmogonic narrative that was compiled in Christian times but which related to events which were said to have occurred in prehistory.

Most people who have read Irish mythology are familiar with the notion of the five provinces. Today, we recognise four - Leinster, Munster, Connacht and Ulster, but in older times there was a fifth. Indeed, the Irish word for 'province' is cóiced, which means a 'fifth'. More about the five provinces presently.

Cosmogony

Lebor Gabála Érenn (LGE) recounts the division and partitioning of Ireland into different provinces by various invaders. This cosmogonic chronicle describes how Partholón's sons divided Ireland into four. The Nemedians, who came after, divided the land into three. The Fir Bolg followed, dividing Ireland into five territories. When the Milesians successfully took Ireland from the Tuatha Dé Danann, they divided the island into two territories – north and south – with Eremón ruling over one and Eber the other. The territories were divided by the Boyne – a river that was to become central to the modern political strife between north and south after the famous Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Here, we see how reality is sometimes seen to echo myth, and this is certainly true in the history of Ireland which has tended to mimic the mythic account which portrays it as a land subject to a sequence of arrivals or incursions.

At the end of one year of the reign of Eremón and Eber, there was a dispute between the brothers and they fought to the death. Having killed his brother, Eremón took sole command of an apparently united Ireland.

The cosmogony of LGÉ seems to imply that the division of the land was something that happened in conjunction with other creative events, such as lakes bursting forth. Seven lakes were created in the time of Patholón, four in the time of Nemed and three during the reign of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Fifth province

But it is the division into five that most interests us here, and the identity of the fifth province with regard to the modern geographical and indeed political divisions of Ireland. LGE attributes this fivefold demarcation of Éire to the Fir Bolg:

As everone does, they partitioned Ireland. And that is the division of the provinces of Ireland which shall endure for ever, as the Fir Bolg divided them.

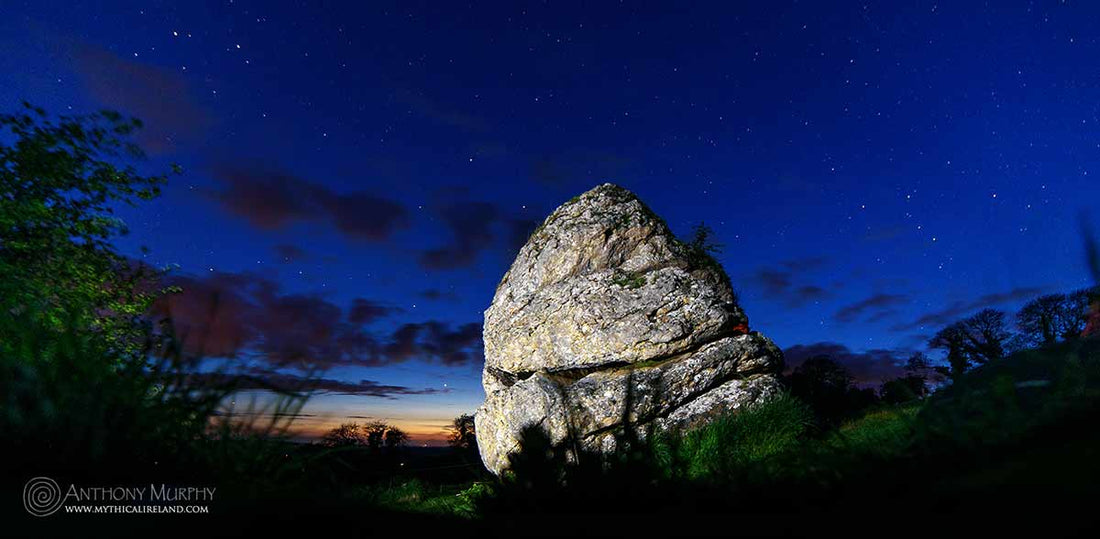

Tradition holds that the provinces met at Ail na Mireann, the 'Stone of Divisions",also known as the 'Cat Stone",on the Hill of Uisneach, which is located in modern-day County Westmeath.

The fifth province – where the other four meet – was called Mide. It is marked by Ail na Mireann, believed in former times to be the geographical midpoint of Ireland. Michael Dames says:

Many scholars think that the elusive fifth [province] stands for something more fundamental. The likelihood is that ever since the Stone Age (and despite numerous boundary changes in detail), Ireland has been subdivided into four provinces, held together by a mystical fifth, territorially elusive, yet vital to the cohesion of the whole sacred array... But since the mythic view of reality declares that efficiency is the outcome of magical accord between the seen and the unseen, there is more to Mide than just simple geometry... Mide, the notional centre of Ireland, was conceived as a point where an umbilical cord attached the country to the womb of the gods, who endlessly created and sustained its existence from above and below.

In The Settling of the Manor of Tara, when Fintan is asked how Ireland had been partitioned, he answered: 'Easy to say. Knowledge in the west, battle in the north, prosperity in the east, music in the south, kindship in the centre.'

According to Rees and Rees, the supernatural Trefhuilngid proceeds to expand on Fintan's statement, describing in detail the attributes of each of the provinces, including the middle:

| WEST (Connacht) |

| LEARNING (Fis), foundations, teaching, alliance, judgement, chronicles, counsels, stories, histories, science, comeliness, eloquence, beauty, modesty (lit. blushing), bounty, abundance, wealth. |

| NORTH (Ulster) |

| BATTLE (Cath), contentions, hardihood, rough places, strifes, haughtiness, unprofitableness, pride, captures, assaults, hardness, wars, conflicts. |

| EAST (Leinster) |

| PROSPERITY (Bláth), supplies, bee-hives, contests, feats of arms, householders, nobles, wonders, good custom, good manners, splendour, abundance, dignity, strength, wealth, householding, many arts, accoutrements, many treasures, satin, serge, silks, cloths, green spotted cloth, hospitality. |

| SOUTH (Munster) |

| MUSIC (Séis), waterfalls, fairs, nobles, reavers, knowledge, subtlety, musicianship, melody, minstrelry, wisdom, honour, music, learning, teaching, warriorship, fidhcell-playing, vehemence, fireceness, poetical art, advocacy, modesty, code, retinue, fertility. |

| CENTRE (Meath) |

| KINGSHIP, stewards, dignity, primacy, stability, establishments, supports, destructions, warriorship, charioteership, soldiery, principality, high-kingship, ollaveship, mead, bounty, ale, renown, fame, prosperity. |

Reading the above, who would live in Ulster? It is interesting to note (as several scholars have undoubtedly done) that the north is central to the ongoing political stife between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom, something that continues to play out long after the Good Friday Agreement and the peace process with the current Brexit impasse. Mythologically, the hero of the Ulster Cycle is Cúchulainn, whose duty among other things in the great epic Táin Bó Cuailnge is to defend Ulster against the armies of Queen Medb. In the Táin, the attribute of "battle" associated with Ulster in the cosmogony of LGE manifests grotesquely with the inveterate and gruesome slaughter carried out by Cúchulainn, who kills the warriors of the other provinces by the hundred.

Sovereignty

The centre province, as indicated by Trefhuilngid, is related to kingship, stability, establishments, prosperity. It shouldn't be surprising, then, to find in Tochmarc Étaín (The Wooing of Étaín) that Dagda, the chief of the Tuatha Dé Danann, had his abode at Uisneach, 'for it is there that [his] house was, Ireland stretching equally far from on every side, south and north, to east and west'.

Uisneach was also where 'men were accustomed to worship Fohla",one of a triune of tutelary goddesses representing the sovereigty of Ireland. Another of this trio is Ériu, and it could be said that symbolically the most significant meeting of the LGE takes place when the sons of Míl, led by their spirital figurehead Amergin Glúngeal, encounter Ériu at Uisneach, the centre province, the omphalos that connects the earthly world to the divine one.

They had colloquy with Eriu in Uisnech. She spake thus with them: Warriors, welcome to you. Long have soothsayers known of your coming hither. Yours shall be this island for ever, and no island of its size to the East of the world shall be better, and no race shall be more perfect than your race, for ever.

She asks if Ireland can be named after her. Amergin says Ériu shall be its name for ever, and indeed Éire is the Irish name for Ireland today.

A philosophical viewpoint

What follows in this brief summary is my own persional philosophical view. There is a calling back to the wisdom of a unifying centre and the fifth province. It has manifested itself overtly in recent years with the reinstitution of the ancient Bealtaine fire festival at Uisneach. The goddess (or more specifically Flaithius/sovereignty) is calling us to recognise that fifth province, the province of the heart and the soul, the province of myth, where our earthly concerns open to a cosmic vista. We are trying to tackle contemporary political crises with our heads. We've left our hearts out of the equation. Critically, Ireland continues to acknowledge only four provinces. But what of the fifth?

Does mythology offer us an insight? In Irish myth, the success and fruitfulness of a king's reign depended upon a sacred marriage (banais ríghe) between the king and Flaithius, represented by the goddess. The omphalos or navel, that which joins the earthly world to the creative womb of the gods, is Ail na Mireann at Uisneach. It seems a strange and incongruous 'province', except that it is far more than a geographic or political territory. It is a symbol, perhaps, of the unification of the subconcious world with the living, physical world – a place, or even a notion, from which metaphors and allegories emerge out of a hidden underworld to manifest in our own telluric lives to aid us in dealing with the many trials of life.

Ail na Mireann perhaps represents the ultimate emblematic fulfillment of a unification or meeting point of provinces – those provinces representing diverse attributes and flaws of the human character and experience. Where else can learning, battle, prosperity and music meet, except at Uisneach? And what better to represent a complete bringing together of the dynamic idiosyncrasies of flawed human nature than an omphalos, a connection to mother, to the creatrix – she who wants to see us lead a full, healthy and sincere life? Critically, our mother would want us to have the means, wits, wisdom and knowledge to overcome the crises of life, at whatever stage of life those situations arise.

Our myths have a powerful pedagogical function. Joseph Campbell listed this as one of the four functions of mythology. Whether we wilfully do so or whether we ignore myth as fanciful fable, we continue to live out our myths. It would be nice if we could learn from them too.

Perhaps what is needed in the current political climate is to catch sight of that fifth, unifying and centering province once again. We need to find our Uisneach. We need to find our Ail na Mireann, the principle of an axis mundi (world axis) that is related to sovereignty, stability and prosperity. We may require attributes from each of the other four provinces to help us overcome political dramas and the critical situations that come to us, sometimes not of our own personal or individual making.

We may need learning and history from the west, contention and hardness from the north, dignity and hospitality from the east and wisdom and subtlety from the south. But none of that will be of any providence if we don't have the high-kingship and stability of the centre.

References

Dames, Michael (2000), Ireland: A Sacred Journey, Element Books (originally published as Mythic Ireland by Thames & Hudson,1992).

Lebor Gabála Érenn, Part V, Section VIII: The Sons of Mil and Section IX: The Roll of the Kings, Irish Texts Society, 2008 (1956).

Rees, Alwyn and Rees, Brinley,1989 (1961), Celtic heritage: Ancient tradition in Ireland and Wales, Thames & Hudson.

Williams, Mark, Ireland's Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth, Princeton University Press.